Different stakeholders* will require different types of engagement on the different issues. People and groups internal to the provider, including staff and students, should be extensively engaged through formal participation in decision-making structures and processes. External partners* should be consulted on decisions, have insight into decision-making processes, and have knowledge of major decisions on the medical program made by the provider. External people and groups with an interest in the process and outcomes of medical training and education, including community groups who experience health inequities and Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander and Māori people and organisations, should be consulted on the decisions that impact on them and should have clear information on how they can engage with the provider. While the level of detail and depth of engagement will depend, members of all three types of stakeholders should be engaged in all of three ways named in standard 1.2.1 (1.2.1).

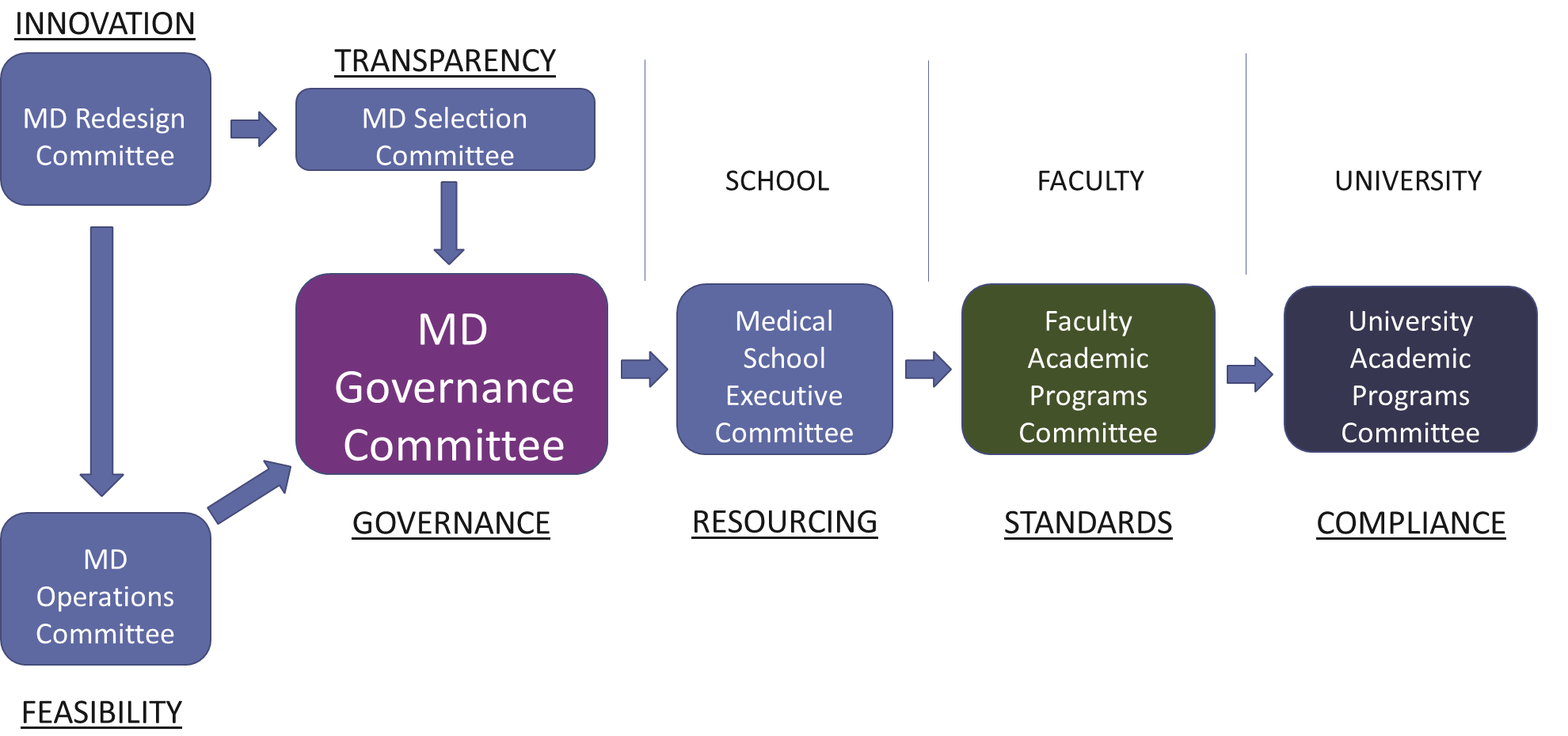

Providers should explain under Standard 1.2: Partnerships with communities and engagement with stakeholders, the strategic approach and mechanisms for engaging stakeholders at a high level. Specific details of engagement should be explained under other standards. For example, student representation should be explained under Standard 1.3: Governance, and direct involvement of community members in teaching and learning activities should be explained under Standard 5.2: Staff resources.

Providers should demonstrate how they collaborate with communities, including Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander and Māori communities, to understand the strengths and challenges of these communities in support of their health care. Providers should show how they contribute towards meeting their communities’ identified needs, including through collaboration with those communities (1.2.1).

Not all partnerships with the categories of organisations named in standard 1.2.2 will be supported by formal agreements. In determining whether a partnership should be supported by a formal agreement, providers should consider the operational, legal, financial and reputational risk of having a partnership without an agreement. Providers should generally secure formal agreements with services that provide structured clinical placements for their students (1.2.2).

To ensure that partnerships with relevant Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander and Māori people and organisations are ‘mutually beneficial’, providers should demonstrate how those partnerships enhance the social accountability and acceptability of the program in line with the expectations of the community. Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander and Māori people and organisations should be engaged through consultation, co-design and inclusion in governance structures, as appropriate (1.2.3).

To ‘promote community sustainability’, providers should not take more resources from Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander and Māori people and organisations than they provide. Providers may achieve this by, for example, paying community controlled health settings to at least cover expenses incurred for placement spaces, funding or contributing to capital works, and/or providing professional development or training opportunities (1.2.3).