‘Fit-for-purpose’ learning and teaching methods means that the selections of methods are aligned with the intended learning outcomes, methods of assessment*, and the intended purpose of learning and teaching (2.3.1).

For providers to ensure that learning and teaching methods create opportunities for students for partnership with patients*, providers themselves should establish partnerships* with patient communities (2.3.2). Details of these partnerships should be explained under Standard 1.2: Partnerships with communities and engagement with stakeholders*.

‘Experience of interprofessional learning’ which ‘foster[s] collaborative practice’ involves a coherent program of planning learning activities, undertaken with students from other relevant health professions, where capabilities required for collaborative practice are deliberately developed.

The ’required level’ of clinical skill development is the level that allows graduates to safely achieve the medical program outcomes* (2.3.5).

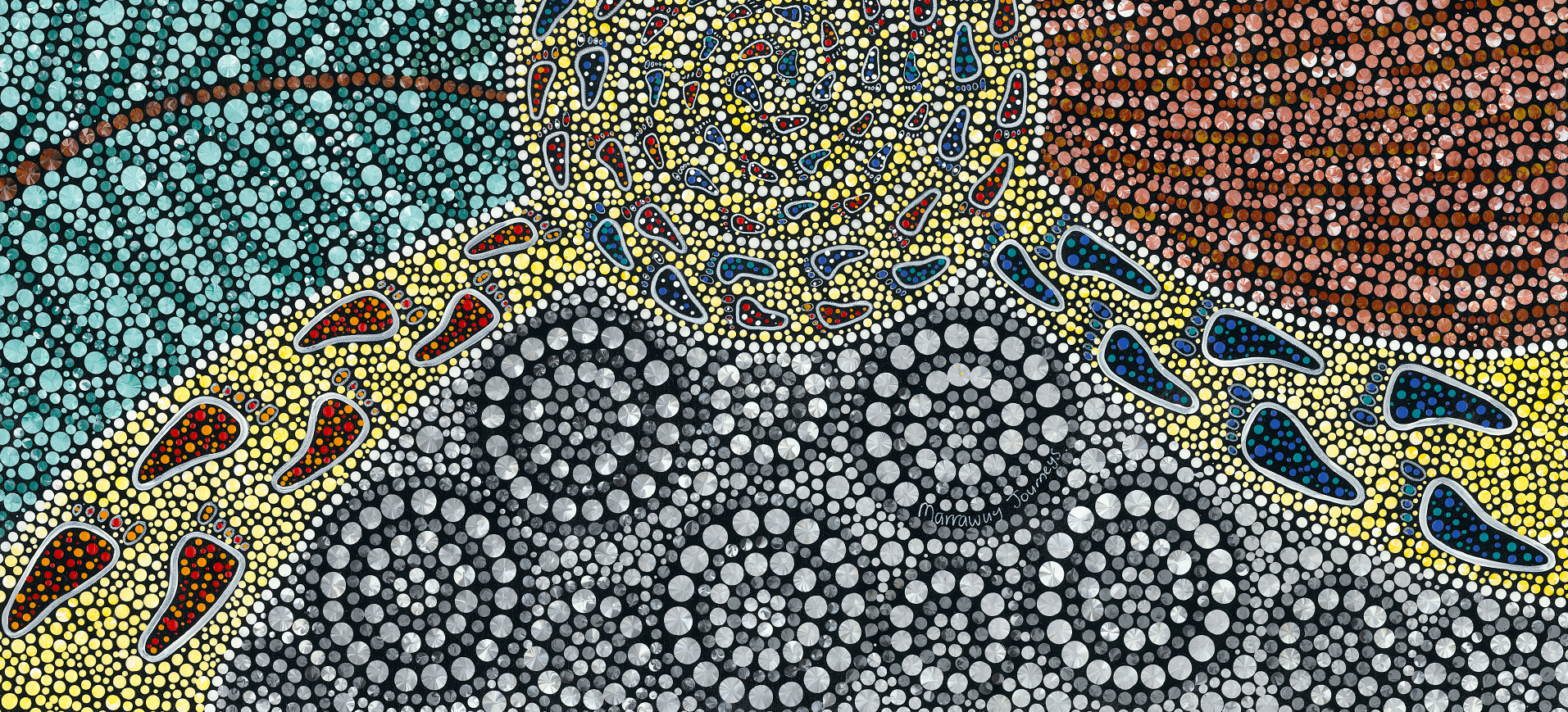

Students’ ‘opportunities to learn about the different needs of community groups who experience health inequities* and Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander and Māori* communities’ should involve members of those communities in learning, teaching, assessment and/or co-design. The ‘different needs’ of these communities includes consideration of intersectionality (2.3.6).

Learning and teaching that ‘is culturally safe’ is informed by Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander and Māori knowledge systems and is spiritually, socially, emotionally and physically safe for learners and teachers. Providers should consider the differing needs of Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander and Māori learners engaging with content, Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander and Māori staff teaching, and Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander and Māori communities interacting with the program. All identities are valued, and there is mutual respect and sharing of meanings and knowledges (2.3.7).

‘Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander and Māori knowledge systems’ that providers should consider in their program include:

- Social and emotional wellbeing.

- Strengths-based discourse.

While the AMC does not specify minimum contact hours or weeks that medical students must spend in learning environments – clinical, campus, community, laboratories etc. – an ‘extensive range of face-to-face experiential learning experiences’ means that a meaningful proportion of the medical program should be delivered in-person, particularly clinical learning (2.3.8).

All students should be able to undertake a range of ‘experiential learning experiences’. Providers should specify which students undertake which learning experiences. All students should have opportunities to undertake experiential learning in both inpatient and outpatient settings. It is noted that not all students will have the opportunity to undertake all experiences offered by the program (2.3.8).

Dedicated end-to-end rural pathways will meet this standard if students within these pathways have sufficient opportunities related to healthcare in a variety of clinical disciplines, relevant across the life span, and situated in a range of settings including health promotion, prevention and treatment (2.3.8).

That learnings experiences are ‘undertaken in a variety of clinical disciplines’ refers to clinical placements being planned and structured to enable students to demonstrate achievement of learning outcomes across clinical disciplines in both general and speciality medicine and surgery, as well as women’s health, child and adolescent health, mental health and primary care. Placements may be integrated (particularly in rural settings) and do not need to be specific to a clinical discipline, but providers should be able to demonstrate how students will gain experience in these clinical disciplines throughout their clinical learning placement (2.3.8).

In pre-internship programs*, the learning needs of students are explicit and central, and the role of the student, as well as their scope of practice within the clinical team, is clearly defined and articulated. The AMC does not specify the content of or minimum contact hours or weeks for pre-internship programs. The provider should be able to justify the content and length of the pre-internship program as sufficient to facilitate a safe transition to internship through consolidation of clinical knowledge and provision of strategies and skills relevant to internship. Providers and training sites should be partners* in ensuring the quality of student learning, assessment and support. Prevocational training providers* are key stakeholders to engage while designing pre-internship programs (2.3.9).